This article was last updated on April 16, 2022

Canada: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

USA: ![]() Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Oye! Times readers Get FREE $30 to spend on Amazon, Walmart…

Sadly, this has become the reality for the majority of us living in the world's advanced economies:

As adults with a lifetime of experience looking at faces, we have no idea whether this person is happy, sad, smiling or frowning given that the most important part of her facial expressions are being hidden by a "face nappy". Humans rely on facial expressions as a key part of their communications with others and, during the COVID-19 pandemic, this means of communication has been completely banished. While it may not seem that serious to those of us who are older, as you will see in this posting, obscuring facial expressions could have long-term negative side-effects on the most vulnerable and young among us.

In 2017, research by neurobiologists Margaret Livingston, Michael Arcaro and Peter Schade at Harvard Medical School examined humans ability to recognize faces and changed the previously held belief that the ability to recognize faces was innate, something that our brains know how to do immediately after birth. The study "Seeing faces is necessary for face-domain formation" is, ironically, available on the National Institutes of Health/National Library of Medicine website. Here is a summary of their findings.

To discover whether seeing faces is necessary for acquiring face domains in the brains of primates, the researchers raised 3 macaques without any experience of seeing faces for the first year of their lives. They also had a control group of 4 macaques which had a typical upbringing, spending time with their mothers during early infancy and then with other juvenile macaques and humans as they aged. The 3 macaques that were hand-raised were bottle fed by humans wearing welders' masks and were provided with an enriched environment of handling and play several times a day along with fur-covered surrogates that were hung from their cages and moved in response to the movements of the macaques. The test animals were also provided with colourful interactive toys and soft towels as part of the researchers efforts to provide them with a responsive and visually complex environment that supported normal socialization. The monkeys were kept in a curtained-off part of a larger monkey room so that they could both hear and smell other monkeys but not see their faces. The 3 monkeys' psychological health was assessed during the experiment and were deemed to be consistently lively, curious, interactive and exploratory. Following the experiment, they were returned to juvenile social groups into which they successfully integrated.

When both the facially deprived and control group of macaques were 200 days old, the researchers used functional MRI to look at brain images which measured the presence of facial recognition patches in their brains and other specialized areas of the macaque brain that are responsible for recognizing four groups of images; bodies, hands, scenery and objects. The experiment was broken into two key parts:

1.) Recognition of faces, bodies, hands, scenery and objects – the control group of macaques which had a typical infant life had consistently developed recognition areas in their brains for all groups of images including faces. In contrast, the 3 macaques who had never seen a face had consistently developed recognition areas for bodies, hands, scenery and objects but had not developed recognition areas in their brains for faces.

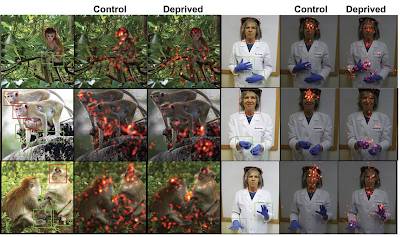

2.) Preference for gazing at faces – when showed an image which featured an image of humans or primates, the control group of macaques preferentially gazed at faces whereas the 3 macaques who had never seen a face preferentially gazeds at the hands. MRI scans showed that the hand domain in the 3 facially-deprived macaques was disproportionately large compared to other domains. Here is a photograph from the study showing where the control and facially-deprived macaques focussed their attention:

Let's close this posting with a quote from the research with bolds being mine:

"We asked whether face experience is necessary for the development of the face patch system. Monkeys raised without exposure to faces did not develop normal face patches, but they did develop domains for scenes, bodies, and hands, all of which they had had extensive experience with. Furthermore the large-scale retinotopic organization of the entire visual system, including IT, was normal in face-deprived monkeys. Thus, the neurological deficits in response to this abnormal early experience were specific to the never-seen category. These results highlight the malleability of IT cortex early in life, and the importance of early visual experience for normal visual cortical development.

A lack of face patches in face-deprived monkeys indicates that face experience is necessary for the formation (or maintenance) of face domains. Our previous study showing that symbol selective domains form in monkeys as a consequence of intensive early experience indicates that experience is sufficient for domain formation.

While in the age of COVID-19 most parents are not masked at all times in the presence of their infant or older children, this research should cause some concern for parents since it clearly shows that primates who are deprived of the normal early life experiences with facial expressions did not develop face domain regions in their brains. One has to wonder what the long-term impact of a steady diet of this:

….and this:

….will be to the physiological and psychological health and normal brain development of young children being raised during the current pandemic.

You can publish this article on your website as long as you provide a link back to this page.

Be the first to comment